By Pepper Parr

By Pepper Parr

January 28th, 2024

BURLINGTON, ON

First in a series

In August 2022 Public Service Canada published a lengthy report on Flood Insurance and Relocation.

The Executive Summary of the report set out four subject areas that were focus points

Executive Summary

A Task Force to Explore Insurance Solutions

A Shared Evidence-Basis for Decision-Making

Key Findings of the Task Force

Living with Water

In August of 2014 the City experienced a devastating flood in the eastern part of the City.

In April of 2019 Burlington declared a Climate Emergency.

In April of 2019 Burlington declared a Climate Emergency.

By 2024 most of the world had come to the realization that we were dealing with a crisis and that not everyone was on board.

The report set out, to some degree, what water means to Canadians. Four out of the five Great Lakes lie between the United States and Canada. They are Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario; the only Great Lake that does not border Canada is Lake Michigan.

The foreseeable future suggests that Canadians must learn to live with water. Yet, the country cannot do this at the expense of safety, fiscal responsibility, or equity.

It is clear from this work that flood insurance solutions for high-risk areas can be designed to meet the Public Policy Objectives; however, each model examined contains trade-offs that must be balanced. It is also apparent that given the amount of flood risk in Canada, none of the insurance models can provide affordable insurance and also be financially self-sufficient, at least in the short term. Even over a longer-term (25 year) transition to risk-based pricing, financial sustainability will continue to be challenged by inflation, significant asset concentration in flood-prone areas, and long-term climate change pressures.

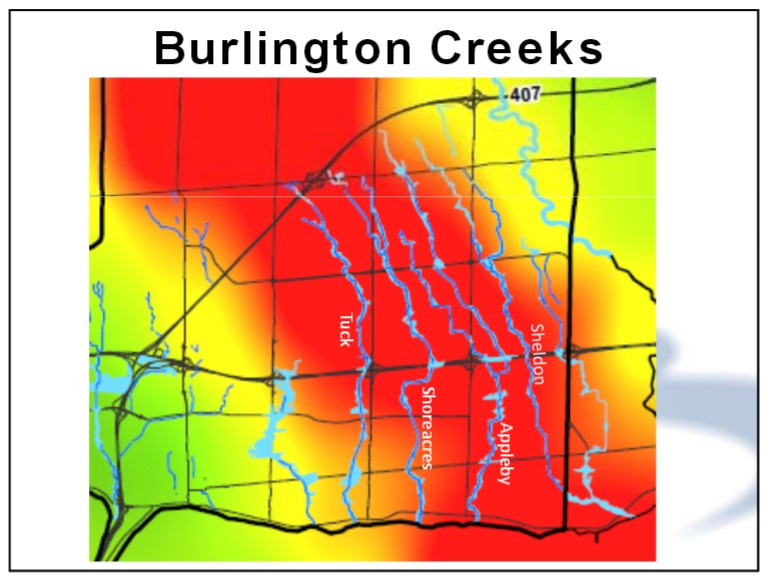

The Canada United States border is shown as a thin red line

Consequently, to live with water, Canada will require more than an insurance solution to address its flood risk landscape. Insurance must be deployed in conjunction with information, investments and incentives at all levels that are designed to reduce flood risk. Such elements include: improved flood mapping and public awareness of flood risk, risk reduction by all stakeholders, improved land-use planning, and climate-resilient built and natural infrastructure. In addition, for an insurance solution to be successful, recovery funding provided to residential properties for flooding though FPT disaster financing programs would need to cease or be restructured to avoid undermining the insurance system. This is an important step towards aligning responsibilities for flood risk.

The findings in this report are meant to provide governments with the foundation to understand the different policy levers and key considerations to be factored into decision-making, and to ensure that any insurance solution strives to effectively meet the defined policy objectives and serve all Canadians impacted by flooding. Particularly, it is important to consider policy options that account for the populations that are disproportionately affected by floods and have lower levels of resiliency to cope with them.

Continuing to advance this work will require coordination and commitment from each stakeholder to exercise their jurisdictional role and develop a way forward for implementation. The collective challenge will be to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good, thereby preventing the implementation of a solution that could nonetheless dramatically improve upon the status quo for Canadians who remain at high risk and who continue to experience tremendous loss from ever-increasing flood events. A new approach to flood insurance will not solve all vulnerability to flooding. However, with a strong stakeholder commitment and decisive action, it could play an important role in empowering Canadians to adapt to flood risk, and building disaster resilience across our nation.

. In recent years, the gap between insured losses and total economic losses has also widened significantly. In 2020, this “protection gap” widened to a record $231 billion worldwide, with around 75% of potential global losses from natural disasters remaining insured with insufficient coverageFootnote 7. The consequences of this are already being experienced across Canada, where disaster costs have risen dramatically in recent years. Before 1995, only three disasters in Canadian history exceeded $500 million (2014 dollars), but from 2013 to 2017, Canada had disaster losses totaling $16.4 billion. Prior to 2009, insured losses from catastrophic severe weather averaged $400 million per year; since then, the annual average has reached $1.4 billion.

The 2014 flood centered on the creeks that were not built to handle the flow of water:

The trajectory of disaster trends poses significant risks to the health and well-being of Canadians, the economy, and the natural environment. Governments and other stakeholders must continue to work together to address the growing impacts of disasters. In 2019, the federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) governments approved the Emergency Management Strategy for Canada: Toward a Resilient 2030 (EM Strategy), which provides a long-term, strategic vision for emergency management in Canada that is aligned with the United Nations Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

The Emergency Management Strategy seeks to guide federal, provincial, and territorial governments and their respective EM partners (including but not limited to: Indigenous peoples, municipalities, communities, volunteer and non-governmental organizations, the private sector, critical infrastructure owners and operators, academia, and volunteers) to build resilience through five priority areas for action:

Enhance whole-of-society collaboration and governance to strengthen resilience;

Improve understanding of disaster risks in all sectors of society;

Increase focus on whole-of-society disaster prevention and mitigation activities;

Enhance disaster response capacity and coordination and foster the development of new capabilities; and

Strengthen recovery efforts by building back better to minimize the impacts of future disasters.

Priority 3 includes as a priority outcome that “FPT governments assist in the development of options for sharing the financial risk of disasters”, which could include “engag[ing] the private sector to develop an affordable private flood insurance model for the entire population, including clear incentives for mitigation of flood risks”.

Flooding – up front and very personal.

In Canada, recent efforts to reduce disaster risk have focused in large part on flooding, given that it is the country’s most common and costly natural disaster. Flooding has caused approximately $1.5 billion in damage to households, property and infrastructure in Canada annually in recent years (approximately $700 million in insured losses and $800 million in uninsured losses), with residential property owners bearing approximately 75% of uninsured losses each. Several million homes in Canada are vulnerable to flooding, and many cannot access adequate insurance to protect themselves. These households must rely on their own resources or limited post-disaster financial assistance from governments or not-for-profit groups to recover from flooding events, which do not fully compensate for all financial losses.

The report runs to 117 pages. The Gazette will cover the fundamentals in a four part series.

The golf course came first and included an infrastructure to manage the flooding. An additional 98 homes threatens the capacity of the infrastructure.

To tighten the focus from a Canada wide viewpoint to a local issue we will frequently turn to the problem the people in the Millcroft community face. That community was built around a golf course that included an infrastructure that was designed to manage the flow of water.

A developer purchased the golf course and then filed an application to build an additional 98 homes that would, in the minds of many in the community damage the infrastructure and result in serious flooding.

They opposed the expansion of additional housing, city council chose not to accept the development proposal and an appeal was filed with the Ontario Land Tribunal.