October 18th, 2024

BURLINGTON, ON

“It is A time of massive anxiety.” Justin Trudeau was talking about Canadians’ economic outlook, pitching the durability of his liberal project to a gathering of global progressives in Montreal last month. “People notice the hike in their mortgages much more than they notice the savings in their child care,” he offered, perhaps implying that in doing so people failed to appreciate all he did for them.

A diagnosis of anxiety fits his own government, too. Mr Trudeau and his party have traversed an arc from heroic to hapless during nine years in office, and today are despised by many in Canada. Less than a quarter of the electorate plans to vote for him. With less than a year to go until a general election, Liberal-party members fear no plan exists to increase that share. They have lost two by-elections in quick succession, as well as the support of their governing partner, the New Democratic Party. As this story was published, a letter was circulating among Liberal MPs calling on Mr Trudeau to stand down. Massive anxiety indeed.

Mr Trudeau became a beacon of morality after he swept to power in 2015, welcoming refugees from war-torn Syria that Christmas. He legalised marijuana, rewarding the record number of young people who had voted for him. He faced down a truculent President Donald Trump to salvage the North American trade pact that is foundational to Canadian prosperity. His government’s annual payment to families of up to C$7,787 ($5,660) per child under six is hailed for lifting 435,000 children out of poverty. After promising child-care subsidies to help more women into work, working-class and younger voters gave him renewed minority mandates in 2019 and 2021.

Three years later those groups have turned on Mr Trudeau. Today both tend to support the opposition, Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives. What went wrong?

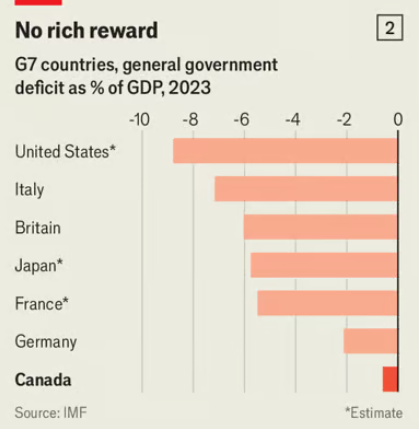

The high cost of housing is central. The cost of owning a home in Canada has increased by 66% since he took office in 2015, with prices rising faster in this century than in any other sizeable OECD country bar Australia. Lack of supply is a problem in many, but is especially acute in Canada. In 2022 the average OECD country had 468 dwellings per 1,000 inhabitants. Canada had 426, a number that has hardly moved in a decade (see chart 1). Mike Moffatt, a housing economist, says a “wartime effort” is needed to triple the current building rate and throw up 5.8m houses in the next ten years. No such luck. In August, Canadian housing starts dropped to an annualised rate of 217,000.

Demand for housing from the large number of immigrants during Mr Trudeau’s decade in power has worsened the crunch. The number of temporary foreign workers jumped from 109,000 in 2018 to just under 240,000 in 2023. The number of non-permanent residents—including temporary foreign workers, students and asylum-seekers—has more than doubled from 1.3m in 2021 to over 3m on July 1st, according to Statistics Canada, representing 7.3% of Canada’s total population of 41m.

The education and health-care systems have also felt the pinch. Universities are bursting with foreign students, often lured by unscrupulous overseas middlemen offering “sham” degrees, according to Mr Trudeau’s immigration minister, Marc Miller. There were 560,000 student visas handed out in Canada last year. Mr Miller is cutting that number to 364,000. “It’s a bit of a mess, and it’s time to rein it in,” he said earlier this year. Some elementary-school teachers flounder, as they grapple with the children of recent arrivals who often speak neither of Canada’s official languages, English and French.

The pain of high housing costs has been compounded by a mediocre economy. Canada suffers from laggardly productivity growth, which has weighed on wages. Investment has been strong in oil- and gas-fields, and in extractive industries more generally, but has been overshadowed by other parts of the economy. Investment in tech, R&D and education taken together as a share of investment is lower in Canada than anywhere else in the G7 club of rich countries.

Canada’s economic ties with the United States have created problems since the end of the pandemic. American spending switched disproportionately to domestic services after lockdowns ended. This left Canadian manufacturers, whose goods had been flying off the shelves, in the lurch. More of the job of powering Canada’s economy, therefore, fell to its services sector, which relies on demand from Canadian households and the government.

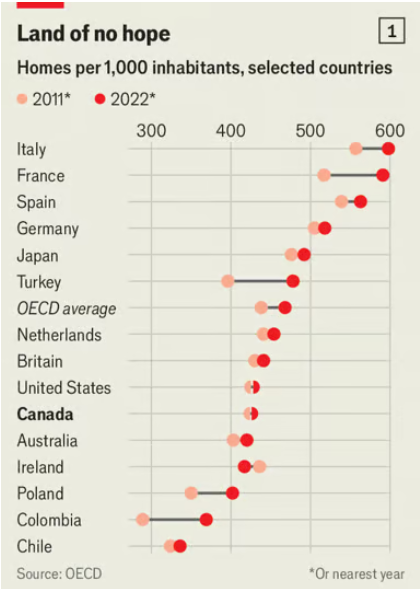

But demand has been throttled by higher interest rates. Monetary policy has had more “traction” in Canada than in the United States, according to Tiff Macklem, the central-bank governor. In the United States, most mortgages are fixed for 30 years, compared with, typically, five in Canada. A greater share of Canadians than of Americans have already seen their mortgage payments rise, although Canadian households bear more debt, relative to income, than anywhere in the G7. They now fork out an average 15% of their disposable income to service debt, up by 1.5 percentage points since 2021, compared with 11% for Americans. And unlike Uncle Sam, Canada’s government has not tried to soften the blow by loosening the purse strings. It ran a budget deficit of just 1.1% of GDP in 2023, compared with 6.3% in the United States (see chart 2).

But demand has been throttled by higher interest rates. Monetary policy has had more “traction” in Canada than in the United States, according to Tiff Macklem, the central-bank governor. In the United States, most mortgages are fixed for 30 years, compared with, typically, five in Canada. A greater share of Canadians than of Americans have already seen their mortgage payments rise, although Canadian households bear more debt, relative to income, than anywhere in the G7. They now fork out an average 15% of their disposable income to service debt, up by 1.5 percentage points since 2021, compared with 11% for Americans. And unlike Uncle Sam, Canada’s government has not tried to soften the blow by loosening the purse strings. It ran a budget deficit of just 1.1% of GDP in 2023, compared with 6.3% in the United States (see chart 2).

Climate change offered Mr Trudeau perhaps his clearest opportunity to blend moral leadership with pragmatism. But he ignored polling showing that while Canadians were concerned about the climate crisis, they were also loth to pay taxes equivalent to a Netflix subscription to fight it. His carbon tax, introduced in 2019, imposed a levy on greenhouse-gas emissions, currently running at C$50 per tonne, scheduled to rise by C$15 annually to reach C$170 per tonne in 2030. Canada’s parliamentary budget watchdog said last week that most households were worse off when indirect costs of the tax were factored in. Mr Trudeau’s failure to find a way to compensate groups who lost out as a result of the tax left it and him vulnerable to attacks from Mr Poilievre; he says the tax will lead to “nuclear winter”, trigger “mass hunger and malnutrition” and compel poor, older people to freeze. Support for the carbon levy has crumbled.

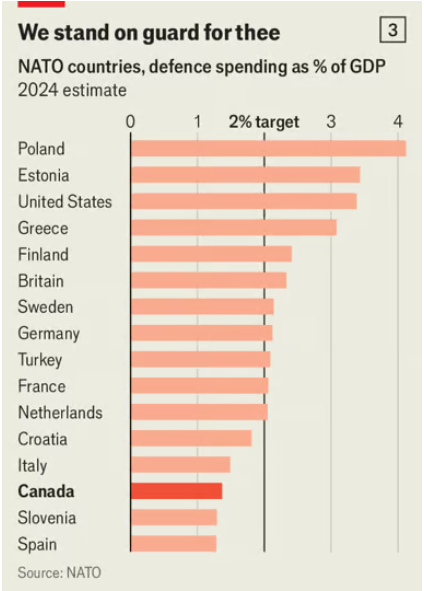

Mr Trudeau’s standing is not helped by the waning under his Liberal government of Canada’s influence in global affairs. When it last tried to win a seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2020, it finished behind Norway and Ireland. It spends just 1.3% of its GDP on defence, far below the 2% required of NATO members, and the pace set by rearming European members facing an expansionist Russia (see chart 3). Mr Trudeau has promised Canada will hit the 2% level in 2032. Meanwhile, its relations with Asia’s two most populous countries, China and India, remain ice-bound. On October 14th India withdrew six diplomats from Canada, the latest move in an ongoing spat between the countries over the murder of a Sikh separatist in British Columbia last year. In the Middle East, Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, does not return Mr Trudeau’s calls.

Instead of adapting to or confronting challenges thrown up by his policies, Mr Trudeau has preferred to attack his critics. He seemed inert as the erosion of his party’s support has accelerated. Some Liberals privately suggest the breakdown of his marriage last year distracted him. In a shuffle aimed at energising his front bench last year more than half his cabinet changed portfolios, but the economic message remained the same: we will continue to deliver “good things” to Canadians. Only recently has Mr Trudeau begun to acknowledge that this fell short. “Doing good things isn’t enough to deal with the kind of anxiety that is out there,” he told the Montreal conference. He still describes his voters’ problems in psychological rather than practical terms.

Boxed out

Mr Poilievre identified that economic anxiety early. This lent him credibility with the sectors of the Canadian electorate who felt abandoned. He has boiled his platform down to a series of simple three-word slogans. He says his first piece of legislation will be to “axe the tax”, ditching the carbon levy. He has yet to outline what his government would do to fight climate change, but polls make it clear that Canadians care far less than they used to. All too many have forsaken Mr Trudeau, and the causes he stood for. ■

Editor’s note (October 15th 2024): This story has been updated to include India’s withdrawal of diplomats.

Correction (October 16th 2024): An earlier version of this article cited a figure of C$50 per tonne as the current level of Canada’s carbon levy. In fact, it is currently C$80 per tonne. Sorry.

If Canada did more spending on Defence…

Imagine hiring new soldiers + sailors and providing college education for officers and skilled technicians. Expanding manufacturing of military equipment at Canadian facilities.

Innovation and design of sophisticated materiel for modern times.

It doesn’t have to be “weapons” – but: surveillance, communications, transport vehicles, aerospace, etc.

Invest in repairing and upgrading old military equipment – helicopters etc.

Canada has a long history of a military presence. An achievement to be proud of.

A history that saw Canada taking first steps, long before our Allies the US entered the combat theatres of WWI and WWII.

Better to invest in ourselves and prepare now – in this world of uncertainty – than to wait until some “surprise” happens.

Plus we would attain our NATO target of 2% of GDP.