By Pepper Parr

By Pepper Parr

September 29th, 2023

BURLINGTON, ON

Truth and Reconciliation – How far have we come?

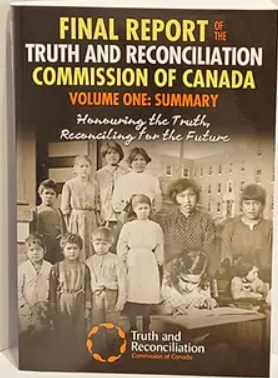

It was a report that opened up public discussion on the residential school issue and the damage that was done to the Indigenous communities.

Are there still people who can’t tell you what Truth and Reconciliation means?

It is now celebrated as Orange Shirt Day

Every child matters Orange T shirts are seen everywhere. How many high school students know what that means?

Phyllis Jack Webstad, whose personal clothing—including a new orange shirt—was taken from her during her first day of residential schooling, and never returned. The orange shirt is a symbol of the forced assimilation of Indigenous children.

Orange Shirt Day was first established as an observance in 2013, as part of an effort to promote awareness and education of the Canadian residential school system and the impact it has had on Indigenous communities for over a century.

The orange shirt now symbolizes how the residential school system took away the indigenous identities of its students. However, the association of the colour with the First Nations goes back to antiquity, the colour represents sunshine, truth-telling, health, regeneration, strength and power.

The Orange T short organization commissions a new design each year.

Today, Orange Shirt Day exists as a legacy of the time when Indigenous children were taken from their homes to residential schools. The tagline, “Every Child Matters”, reminds Canadians that all peoples’ cultural experiences are important.

When high school students ask – what do they mean when the Indigenous community say “we are a First Nation”?.

The use of the word Indian is no longer acceptable. It has been used in some reports because of the historical nature of an article and the precision of the name. It was, and continues to be, used by government officials, Indigenous peoples and historians while referencing the school system. The use of the word also provides relevant context about the era in which the system was established, specifically one in which Indigenous peoples in Canada were homogeneously referred to as Indians rather than by language that distinguishes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. Use of Indian is limited to proper nouns and references to government legislation.

There are dozens of web sites with very good material on what we did to the Indigenous population. This web site has a collection of stories told by Indigenous people. Worth spend some tine on.

Shortly after Confederation in 1867, the ministers inherited the responsibility of advising the Crown on the treaties signed between it and the First Nations of Canada. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was faced with disparate cultures and identities and wanted to forge a new Canadian identity to unite the country and ensure its survival. That was the thinking at the time.

Demonstrators topple a statue of Sr John A. MacDonald in a public square in Montreal.

Macdonald’s goal to absorb the First Nations into the general population of Canada and extinguish their culture. In 1878, he commissioned Nicholas Flood Davin to write a report about residential schools in the United States.

One year later, Davin reported that only residential schools could separate aboriginal children from their parents and culture and cause them “to be merged and lost” within the nation. Davin argued that the government should work with the Christian churches to open these schools.

The government began funding Indian residential schools across Canada in 1883, which were run primarily by the Roman Catholic Church the Anglican Church, United Church of Canada, the Methodist Church, and the Presbyterian Church.

When the separation of children from their parents was resisted, the government responded by making school attendance compulsory in 1894 and empowered the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to seize children from reserves and bring them to the residential schools.

One of the residential schools in western Canada.

When parents came to take their children away from the schools, the pass system was created, banning Indigenous people from leaving their reserve without a pass from an Indian agent.

Conditions at the schools were terrible, schools were underfunded and tuberculosis was rampant. Over the course of the system’s existence—more than a century long—approximately 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada issued its report in 2008 reporting deaths of approximately 3,200 children in residential schools, representing a 2.1% mortality rate. Justice Murray Sinclair, the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission later stated that the true number of deaths could be as high as 6,000.

Most of the recorded student deaths at residential schools took place before the 1950s. The most common cause of death was tuberculosis, which was also a common cause of death among children across Canada at that time.

Some residential schools had mortality rates of 30%.

Girls in a residential school classroom.

Dr. Peter Bryce reported to the Department of Indian Affairs in 1897 about the high student mortality rates at residential schools due to tuberculosis. Bryce’s report was leaked to journalists, prompting calls for reform from across the country; the recommendations were largely ignored.

Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, who supported the assimilation policy said in 1910 said: “it is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habitating so closely in these schools and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is being geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem.”

In 1914 he added, “the system was open to criticism. Insufficient care was exercised in the admission of children to the schools. The well-known predisposition of Indians to tuberculosis resulted in a very large percentage of deaths among the pupils.”

Many schools did not communicate the news of the deaths of students to the students’ families, burying the children in unmarked graves; in one-third of recorded deaths, the names of the students who had died were not recorded. Sexual abuse was common and students were forced to work to help raise money for the school.

By the 1950s, the government began to loosen restrictions on the First Nations of Canada and began to work towards shutting the schools. The government seized control of the residential schools from the churches in 1969 and, by the 1980s few schools remained open. The last school closed 1996.

We have been working at this for a long time.

In 1986, the United Church of Canada apologized for its role in the residential school system. The Anglican Church followed suit in 1992. Some Catholic organizations have apologized for their role in the residential school system but the Roman Catholic Church had not formally apologized for its role in the residential school system.

In 1991, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was formed to investigate the relationship between indigenous peoples in Canada, the government of Canada, and Canadian society as a whole. When its final report was presented five years later, it led the government to make a statement of reconciliation in 1998.

Former Prime Minister during an apology he issued to the Indigenous Community in Canada. The event took place on the floor of the House of Commons

Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized in 2008, on behalf of the federal Cabinet, for the Indian residential school system and created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada to find out what happened at the schools.

The commission released its final report in 2015. It found that the Indian residential school system was an act of “cultural genocide” against the First Nations of Canada, as it disrupted the ability of parents to pass on their indigenous languages to their children, leading to 70% of Canada’s Aboriginal languages being classified as endangered.

It found that the deliberately poor education offered at the residential school system created a poorly educated indigenous population in Canada, which impacted the incomes those students could earn as adults and the educational achievement of their children and grandchildren, who were frequently raised in low-income homes. It also found that the sexual and physical abuse received at the schools created life-long trauma in residential school survivors, trauma and abuse which was often passed down to their children and grandchildren, which continues to create victims of the residential school system today.

Getting to the point where the country could put all this behind was a tortuous journey. In 2017 Minister of Indigenous Services Jane Philpott and Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett encouraged people across Canada to participate in this commemorative and educational event. The following year, the Department of Canadian Heritage and Multiculturalism announced that it was considering tabling a bill in Parliament to establish a statutory holiday that recognized the legacy of residential schools; September 30 was one of the dates considered.

The Heritage Committee chose Orange Shirt Day, and Georgina Jolibois submitted a private member’s bill to the House of Commons, where it passed on March 21, 2019. However, the bill was unable to make it through the Senate before parliament was dissolved ahead of an election.

The Heritage Committee chose Orange Shirt Day, and Georgina Jolibois submitted a private member’s bill to the House of Commons, where it passed on March 21, 2019. However, the bill was unable to make it through the Senate before parliament was dissolved ahead of an election.

During the subsequent parliamentary session, Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault tabled a new bill on September 29, 2020, proposing Orange Shirt Day become a national statutory holiday. The new holiday would be officially named the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

On May 28, 2021, the day after it was reported that the remains of 215 bodies were discovered in an unmarked cemetery on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, all parties in the House of Commons agreed to fast-track the bill, which passed in the House by unanimous consent. The bill passed the Senate unanimously six days later and received royal assent on June 3, 2021.

The legislation made September 30th a statutory holiday for federal government employees and private-sector employees to whom the Canada Labour Code applies.

The first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation federal holiday in 2021 was marred when it was learned that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had been invited to spend the day with the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc nation, near the place the first Indian residential school unmarked graves were discovered.

Trudeau ignored the invitation, and his schedule showed him having meetings in Ottawa that day. However, Trudeau instead took an unannounced private holiday in Tofino, British Columbia, attracting widespread criticism from the public and media alike. Kúkpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc described his lack of attendance as a “gut punch to the community.”

There is on balance a better public understanding of the residential school issue and the damage that was done. There is a process of healing taking place and an acceptance of the Indigenous population that didn’t exist five years ago. But we are not there yet.

Why do we accept that hundreds of Indigenous communities still do not have potable water?

Gord Downey calling out Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at a concert in Kingston, Ontario

When I talk to people and ask if they would agree to being taxed one dollar a month that would be set aside to ensure that every Indigenous community has potable water I have yet to hear someone say – I don’t want to do that. The public is ready to do more.

The calling out of the Prime Minister at a Gord Downey concert in Kingston Ontario is not something the public had ever seen or heard in a CBC nationally broadcast event.

We have come a long way – but there is still a long way to go. At least now we have momentum.

Burlington Mayor Marianne Meed Ward has been an admirable and consistent advocate -doing everything she can to keep the issue in front of the public.

Related news story:

Today was planned as a family Thanksgiving Dinner up North. . We are not always good at keeping track of the date and actually what day it is at times, a senior thing we are told.

Our first clue was the City closing on Friday, thank you for doing that. We changed our celebration to tomorrow and will visit the Curve Lake Cenotaph and spend some time just giving thanks that the recognition has begun and meditating on how we can do our bit to never forget such things as the founding sector of our country do not all have such basics as potable water. Whereas lots of the community we live in, enjoy such things as walk in spa baths etc.

We must all continue to ensure o7r governments, all of them, must do more to bring basics of life and equitable justice to all Canadians.

We give thanks for our first elected Indigenous Ptrmiere. Surely his contact with all other Premieres will help promote resolution of the potable water for all issue.

How far have come?…

Fad apology/recognition delivered like a sick cliche at the start of city council meetings, thanking native predecessors for the great job they did as stewards of the land they we now call ours and bury under asphalt and dumps.

And oh yeah… those band wagon orange t-shirts manufactured by little brown child labourer hands for pennies a day (only $19.99 at Canadian Tire… for real).