June 10th, 2017

BURLINGTON, ON

Rivers and his wife are on a volunteer teaching course in Ukraine. As part of this trip he will be visiting a Canadian Armed Forces Base and reporting on part of Canada’s role in that part of the world.

He will return at the end of June and give Gazette readers his take on all the changes that are taking place in this country at both the federal and provincial levels.

It’s why treating your children to French Immersion will not make them bi-lingual. They need to sleep with the other language, as a former Canadian bi-lingual commissioner once mused. You need to be able to live it, to experience it. So that is what I’m doing over here in Ukraine – helping Ukrainian children to live extemporaneously in our culture. And I’m not alone. There are over 600 volunteer teachers from 140 countries, including a former Russian, all participating in an initiative called GoCamps.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Ukraine declared its independence, along with all the other Soviet republics. But 70 years of communism had created a culture of passive dependency such that the new nation was reluctant to embrace the changes needed for it to become a fully independent state. That would require abandoning the Russian symbols of authority, its language and religion in particular.

From the Tzars to today’s Vlad Putin, Russia’s leaders have tried to eliminate the traditional language and culture in the lands they occupied. And Ukraine was no stranger to that policy. Ukrainian is a slavic language similar to Russian in that it is based on the almost cryptic Cyrillic alphabet, where the B is a V and the N is a P and the P is an R and the number 3 is a letter. It is very confusing and difficult for we English speakers, and I’m sure the opposite is true.

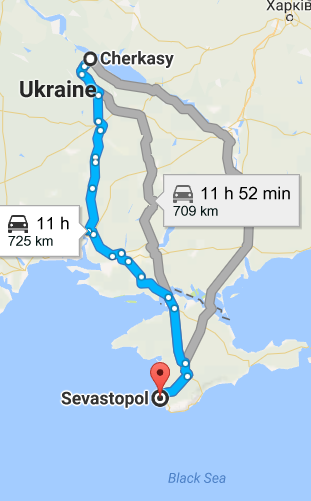

I’m teaching in the industrial city of Cherkasy, some 120 kms south of Kyiv on the expansive Dnieper River. Of the 300,000 people living here it is difficult to find anyone on the street who can speak more than a few words of English, which was likely learned from a TV show or western pop song. Most street signs and restaurant menus, though presumably once in Russian, are almost exclusively in Ukrainian script now, making getting around the city a challenge. Even getting a taxi is difficult since I’ve yet to find a dispatcher who understands either English or my feeble Ukrainian.

Despite that, I am impressed with the high level of English usage among the students at the school I’ve been attending, and their desire to better understand the language and culture that I bring with me. Ukraine’s goal is to eventually replace Russian with English as a second language. I have noticed, in the year since I was last here, how the government has removed Russian language timetables in railway stations – a step in that direction.

There is a segment of the population which would be just as happy to keep Russian but they are becoming a smaller proportion every year and with every new survey taken. It has taken Ukrainians a quarter century to finally decide that they would be better off with memberships in the EU and NATO, something that has held them back from joining previously. It is the youth, the new generation, who more than any others are now making that claim. And for those in doubt about the critical need to improve national security they only need consider what happened to Crimea.

Protection of the Russian language became the official raison d’être for the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Dunbas, in south-eastern Ukraine. Yet despite an active war, ongoing in the east of the country, which has killed over 10,000 people, it was hard to sense animosity towards Moscow. In part that may be due to the long fraternal and historical association between the nations. It might also reflect embarrassment at having failed to defend themselves from the people they once believed were supposed to be their friends, even family.

Ukraine is a politically sensitive part of the world. Russian navy ships moored in the bay of the Crimean city of Sevastopol, Ukraine. Assault teams in speedboats and helicopters have captured a Ukrainian ship in Crimea and moved it to Russian military port

There are five million ex-pat Ukrainians living in Russia and for those who can still recall living in the USSR, the border is an inconvenience. Despite the murderous aggression of Mr. Putin’s crowd, Ukraine still buys some goods from Russia, like uranium for its Soviet built nuclear power plants. And given the degree of Russian espionage and attempted sabotage in Ukraine it is bizarre that ordinary Russians still have visa-free access.

I met a young woman from Cherkasy who was completing her master’s degree at an oil and gas technical college in Moscow. For her the future was about working and living there, given the dim economic opportunities she sees in her home town at the moment. She was having to take the train back to Moscow since the airlines have mostly stopped flights there on account of the war.

For her it’s like that war is with somebody else as she continues business as usual in Russia, a nation where half the people consider Ukraine enemy number one and who are responsible for the death of thousands of Ukrainians. It is hard to fathom how her desire for a good education has overtaken what I’d consider her patriotism. It is odd that there seems to be no concern by her family or friends over her personal security in a Russia that regularly imprisons Ukrainian nationals for crimes called extremism, as it did recently with the chief librarian of the Ukraine Library in Moscow.

I met a family displaced by the conflict in Donetsk and forced to move personal and presumably business interests to the nation’s capital in Kyiv, leaving home and property behind. I would have expected outright anger and outrage, but none of that was apparent in our discussions. And even when the discussion came up there was a puzzling reluctance to blame the Russians.

Ukraine’s history as a nation predates much of Europe, and by centuries Russia, its ungrateful birth child. Its fertile productive valleys and plains have made it the object of conquest. Once a powerful monarchy Ukraine’s invasions, first by the Mongols, then by various other nations, including Austria, Germany, Turkey, Poland and Russia. And given its endowment, agriculture is still the life blood of the nation, generating the greatest export revenue.

Unlike Russia which is geographically more Asian, Ukraine has always been a European nation. And Ukrainians are slowly, too slowly for many now, coming to a consensus that their future, national security and pathway to prosperity, like that of neighbouring Poland, lies in the EU. And for that, in addition to retaining their own rich language and culture, they need to communicate and share the languages of with their new western partners and English above all.

…….to be continued.

Ray Rivers writes weekly on both federal and provincial politics, applying his more than 25 years as a federal bureaucrat to his thinking. Rivers was a candidate for provincial office in Burlington in 1995. He was the founder of the Burlington citizen committee on sustainability at a time when climate warming was a hotly debated subject. Tweet @rayzrivers

Ray Rivers writes weekly on both federal and provincial politics, applying his more than 25 years as a federal bureaucrat to his thinking. Rivers was a candidate for provincial office in Burlington in 1995. He was the founder of the Burlington citizen committee on sustainability at a time when climate warming was a hotly debated subject. Tweet @rayzrivers

Background links:

GoCamps – Russia and Ukraine – Russian Speakers – Ukrainian Language –

Entirely naive when it comes to relations between Russians in Russia and Ukrainians in Ukraine, I found it surprising that the former hate (too strong, perhaps–OK half of them) the latter while the latter appear mostly “OK” with the former. If state vs. state, yeah, that’s a world-wide phenomenon but citizenry vs. citizenry seems *unique* (in the truer sense of the word). Did I get your thoughts on this?

Thanks, Ray, for the report and your and your spouse’s commitment. Thanks too for mentioning the difficulty of survival in a land where you don’t speak the language (that challenge hit me like a ton of bricks during each of my two trips to Central Asia).

BB

I enjoyed this article Ray and look forward to part II. Kudos to you and Jean for volunteering you time and talent, compassion, enthusiasm, etc. etc.

Very well done, Ray!

This is exemplary and fascinating in many ways and I can’t fully express the admiration I have for you and your wife. However, the anthropologist in me still has some uneasiness over the long held notion – as directed toward the American Peace Corps, that teaching another language inescapably means insinuating another culture into the recipient culture. Is this concern recognized? And, if so, how is it addressed?

As I’ve said before, my Ukrainian students were always Top of the Class. I can only imagine the immense satisfaction one must derive from interacting with these highly principled and world wise people. Long suffering, they are the epitome of moral fiber and strength.

Ray, what a completely different perspective on this very complex issue – thank you

Ray, A very interesting and informative article. Good for you and your wife to be part of this educational endeavor.

Will