By Pepper Parr

By Pepper Parr

June 13th 2106

BURLINGTON, ON

Halton Board of Education trustees will this evening hear from citizen delegation on what they would like to see in the way of a French immersion program for the 2017-18 school year.

Staff have recommended:

Grade 2 Entry into French Immersion at both dual and single track schools with 100% intensity for the first year and reduced intensity after that as shown:

Gr 2 – 100% intensity

Gr 3 – 80% intensity

Gr 4 – 50% intensity

David Boag, Associate Director of Education for Halton Board of Education – the man carrying the ball and gathering research for th trustees.

“Delaying entry into immersion till Grade 2 and having kids learn French the whole day instead of half when they start. That way, officials hope, parents will think more seriously about whether to put their kids in the program. It’s a sensible idea that could help ease the bandwagon effect – gotta do it or my kid will lose out – that is overwhelming boards.

Of the 57 Grade 1 kids at Tom Thomson Public School in Burlington, Ontario, 53 are in French immersion. The remaining four are in Ms. Amanda Heilesen’s split Grade 1 and 2 class. KEVIN VAN PAASSEN/for The Globe and Mail

This is one of the few occasions when staff does not direct the elected trustees. Many meetings were held, lots of discussion and a three inch binder of research and the trustees were told – they were on their own.

Halton is trying to figure out how to meet the demand from parents along with the limitations on the school/classroom structure and the difficulty in finding the number of qualified French language teachers. Their problem isn’t helped by the price of housing in Burlington – that much touted Best mid-sized city in Canada isn’t going to do anything for us either.

What do the pundit think? There were two exceptionally good columns in the Globe and Mail recently from which we have pinched shamelessly.

Margaret Wente, a regular columnist at the Globe had this to say:

No wonder Canadian parents have gone crazy for French immersion. Who wouldn’t want to raise a bilingual kid? Across the country, demand is soaring through the roof. Schools are scrambling to cope. In some districts, 25 per cent of the primary-school kids are in French immersion. School officials say there would be far more if they could only find more teachers.

Trustees Papin, Oliver and Grebenc

Just one problem. Well, several, actually. For many parents, French immersion is a way to game the system. It filters out the kids with behavioural problems and special needs, along with the low achievers. In short, it’s a form of streaming. Most French-immersion students are from affluent, high-achieving families that work hard to give their children an edge. And who can blame them? It sure beats forking over $27,220 a year for the Toronto French School (and that’s for kindergarten).

Unfortunately, this selfish but entirely natural parental tendency is at total odds with the gospel of the Canadian school system, which strives to be equal and inclusive above all else. For schools, “streaming” is a dirty word. We are constantly assured that high-performing kids actually do better in classrooms that include all those other kids. And vice versa.

This tension between the school boards and the parents has created an impossible dilemma. Some schools’ English-language programs are being hollowed out. In dual-track schools, they now have a much bigger ratio of disadvantaged, behavioural, etc. kids than the French programs do. The schools are being accused of entrenching inequality. As one immersion advocate told Maclean’s, “If we’re going to offer this program, how can we justify it if we don’t give kids – from whatever background – the tools they need to succeed?”

Today, the idea of French immersion as a magic smart pill is virtually unquestioned.

Sadly, there’s not the slightest shred of evidence that French immersion has accomplished any of its lofty goals. After 40 years of ever-expanding immersion programs, the percentage of Canadians who can speak both official languages has dropped. At two of the Greater Toronto Area’s largest school boards, half of French-immersion students bail out by Grade 8. By the time they graduate high school, only 10 per cent achieve proficiency in French (which is not the same as fluency).

The reasons for this miserable success rate are no mystery. Their entire world outside the classroom immerses kids in English. They play in English. They live in English. Everybody they know speaks English. If you want them to be bilingual, you’d better take them to live in France or Quebec – or at least make sure you’re married to a French speaker.

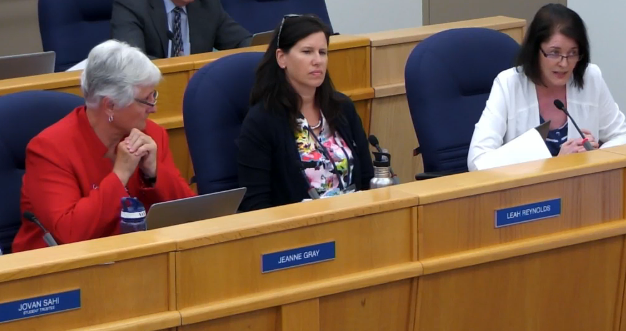

Trustees Gray, Reynolds and Collard

The downsides to French immersion, though seldom mentioned, are also real. Kids who struggle with English will also struggle with French – and who needs that?

Yet the dream lives on. As enrolment shrinks, school boards are desperate to keep parents happy so that they don’t defect from the public system. Like all-day kindergarten – which was also supposed to make kids smarter – French immersion turns out to be too good to be true. But too many people have too much invested in it to say so.

Marcus Gee who also writes a column had this to say:

French immersion is a wonderful thing in theory. Plunge kids into French in their early years, when their brains soak up language like a sponge, and they will emerge as confident French speakers. That will be good for them, making them more rounded people and giving them a shot at jobs where being bilingual is an advantage, and good for the country, helping bring the two solitudes of French and English together.

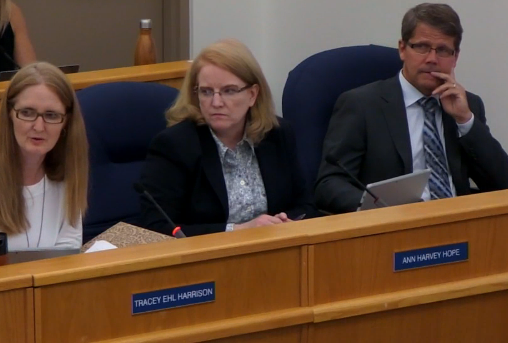

Trustees Harrison, Harvey-Hope. Associate Director of Education David Boag is on the right.

In practice, it hasn’t quite worked out that way, for several reasons. First, kids in immersion aren’t really immersed. The moment they are out the door and into the playground, they are speaking English, not French. In a city such as Toronto – or Edmonton or Vancouver or just about anywhere outside of Quebec – there just aren’t that many opportunities for most kids to use their French outside of school. Even in the classroom, few teachers can enforce a French-only rule at all times.

Second, it’s hard to find French-immersion teachers. The shortage is chronic. Schools scramble to fill immersion teaching posts and end up with a lot of teachers who can’t teach, can’t speak very good French or can’t do either.

Third, many students drop out of immersion as the years pass, some because they aren’t thriving in the French stream, others because they are going to specialty schools that don’t offer immersion. Even those who stay often don’t acquire good French. A surprising number do French for the whole 13 years, from senior kindergarten to Grade 12, and still can’t have more than a halting French conversation when they graduate.

That points to another problem with immersion: It has become a privileged island in the school system, populated disproportionately by kids from better-off families. It is the more educated, more involved parents who tend to choose immersion for their kids, hoping to give them an advantage within the hit-and-miss public system. Immersion classes tend to be whiter than the norm, with fewer students from immigrant families. In some schools, people come to view the English stream as second-rate, a place where poorer kids or kids who struggle in school end up. It’s the kind of division that a multicultural city that prizes equality wants to avoid.

Director of Education Stuart Miller, Chair Kelly Amos and Vice chair Kim Gervais

You can’t blame parents for wanting the best for their children. You can’t blame school boards for wanting to accommodate them either. The goal of French immersion – to give more students command of the country’s other official language – is still a noble one. Knowing a second or third language, a commonplace for Europeans, is an obvious asset in the age of globalization (though Mandarin might be a smarter choice). All my kids say that, whatever the ups and downs of immersion, it gave them a good grounding in French and broadened their horizons.

But the whole program needs a good hard look. Enrolment in immersion is soaring. School boards are struggling to meet the demand. It’s a good time to examine whether it is working as it should.

Will the trustees from Burlington, Oakville, Milton and Halton Hills find a way to meet the mushrooming demands of the parents, the needs of those children who are not cut out for French Immersion and the and at the same time be able to see the bigger picture?

This is not what any of them expected when they ran for public office. They are going to be fully tested with this issue. Fortunately there are a number of wise women on the board. There are enough of them to make the right decision.

They will decide what they want to see done at a meeting on June 15th, after they have heard all the delegations.