By Staff

By Staff

September 14th, 2021

BURLINGTON, ON

The Gazette recently published an article on the tax rate that applies to quarries. There is a link to that article below.

The article came out of a comment the Mayor made at a Standing Committee when she said quarries are taxed as farms – and farms have a very low tax rate.

The Ontario Stone, Sand & Gravel Association (OSSGA), lobbyists for the aggregate industry, took exception to the article and sent us the following:

The assessment of property tax in Ontario is a complicated business. Likely we all agree – too complicated. That said, OSSGA believes there is a fair and equitable system currently in place.

We note that the Burlington Gazette states they “believe fervently that an informed population can make informed decisions.” We agree, and that is why a deeper understanding of the tax environment is needed to understand that the aggregate industry does in fact pay its fair share. It likely won’t come as a shock to your readers that politicians don’t always tell the whole story.

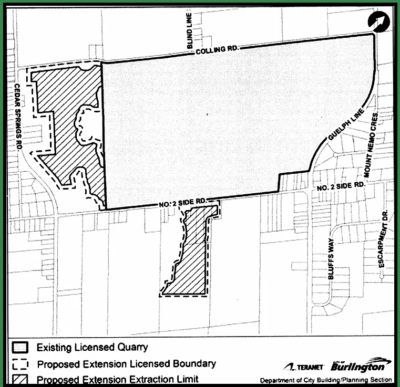

The current operating quarry in Side Road # 2 in rural Burlington

The issue of a fair and equitable Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC) valuation system for aggregate is not new. From 2005 to the present there has been a full pendulum swing from what the industry would consider reasonable rates, to excessive rates, and back to reasonable rates again.

To assess pits and quarries MPAC uses a cost-based methodology that assigns a Class 5 farmland rate plus a licensing cost to account for the investment in the land to get a licence allowing for future extraction. This calculation is used to determine the ‘value’ of the land – and then an appropriate ‘tax’ classification is applied based on how the land is being used. For example, if a portion of a licenced area is being actively used for extraction – it is taxed at an industrial rate (far higher than a farm tax). If it is currently being farmed, it is taxed at a farm rate. If there is no activity at all on the land, it may be taxed at a residential rate. This methodology was agreed to by the municipalities.

In 2016, after eight years of consultation and mediation between aggregate producers, municipalities and MPAC, more than 500 appeals were finally settled. However, it appears not all municipalities were happy. Some were banking on the excessive rates that they are now calling ‘lost revenue’.

Nelson Aggregates has filed an application for an extension of their license and set out places where they want to expand.

Hence the disagreement continues. The new valuation system has been challenged again by Wellington County. The hearing has taken place and a decision is expected in the coming weeks. But in the meantime, politicians accusing the industry of not paying their fair share are not telling the whole story!

One final point. When speaking about revenues received from the aggregate industry, municipalities typically fail to mention (and there was no reference to it in your article), that the aggregate industry also pays a per tonne aggregate levy. In 2020, the amount of the levy was $25 million Province-wide. Dollars that help pay for roads and other infrastructure. No other industry pays such a levy.

We encourage your readers to learn more about the industry by visiting GravelFacts.ca.

The letter was submitted by Norman Cheesman Executive Director, Ontario Stone, Sand & Gravel Association.

Related news stories:

Mayor thinks quarries are being taxed as farms\

Suppose our City needs 100 tonnes of gravel to build a road.

According to the OSSGA, the levy is 21 cents a tonne

Therefore 100 tonnes = a levy of twenty bucks.

That $20 gets passed onto the buyer – in this case, the city.

So the city ends up paying the levy – a portion of which goes back to the Gravel Industry.