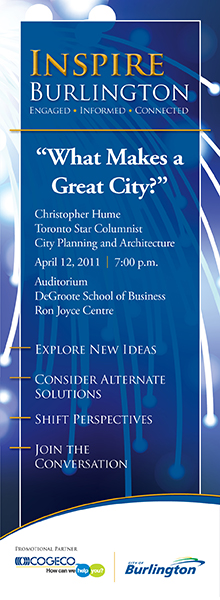

BURLINGTON, ON November 26, 2011 – It was both a lecture on the health service delivery system we have and another look at what the Mayor does as he develops ideas and consensus in the minds of the citizens of Burlington. The event, the Mayor`s Inspire series of lectures, used to be held at the McMaster DeGroote school of business on the South Service Road but got moved to the Community Studio Theatre in the Burlington Performing Arts Centre when that space became available. It may be moving again because this last session was basically a sold out event.

Speaker at the Mayor's Inspire series Andre Picard outlined the way health is delivered and how that delivery could be improved.

Andre Picard, Health reporter for the Globe & Mail came to talk about health care and started with a 20 minute overview of how the government got into the public health business and where we are today – and in the process dispelled a lot of myths. The one that really grabbed me was the fact, according to Picard (and he tends to know the numbers side of the health business) that the government spends on average $15. a day to provide health services for Canadians. That`s all it costs ? – fifteen bucks a day ?. As Picard put it – “you spend that much a day on those latte coffees”.

The audience was taken through a historical tour – the first medicine was delivered by the Ursaline nuns in Quebec. Jeanne Mance opened the first hospital in Montreal and right up to the first world war it was charities for the most part that provided public health. The 1918 Spanish flu that took 60 million lives brought about the need for government to get into the business of providing health services for the public.

The outbreak of polio after the second world war and the prevalence of tuberculosis brought the government into the health business. It started in Saskatchewan where Tommy Douglas said a family should not have to lose the farm to pay the medical bills.

And today we have 15 jurisdictions managing health care that is supposed to be delivered under five prime principles set out in the Canada Health Act. Few remember what those five principles were and few of the five are actually met. Portability was one – the medical health we have really isn’t portable from province to province, but if you are sick in your own province you will probably get the care you need. Sometimes you have to fight for it and it often fails the public it is supposed to serve – but it is what we have.

The hospitals we have today, argued health writer Andre Picard meet few of the needs that an aging population faces.. He advocated for community level service delivery.

The JBMH, due for a major upgrade in 2013. The city has $20 million of its portion of the cost in the bank. Is the upgrade really the best thing for the city'

Picard argues that the hospital of the 21st century is a very complex building and are very expensive to operate. We keep people in these hospitals at a close to exorbitant cost, he said, when there are much less expensive places to put people where better medical service can be delivered.

Our hospitals, according to Picard cannot be everything to everyone. We have to have the right people in the right places and a hospital for someone who should be in a setting where they can get the service and support they need – that is the direction we are going to have to go in.

Picard told his audience that he didn`t think there was a lot of fat in the way hospitals are run but that he didn’t think there was much in the way of efficiencies either and that there was way too much bureaucracy.

The doctors, commented Picard, are doing very, very well under the fee for service system the government put in place, but it isn’t a very efficient way to spend the health care dollars, and as Picard put it “they have their sticky little fingers in everyone else’s pie”. There are many things doctors are doing that could be done much more cost effectively by well-trained nursing staff, but the fee for services model we use has doctors doing as much as they can – that’s how they get paid.

Picard told his audience that Canada has 5,000 more doctors now than it had three years ago and that “we just cannot keep growing the medical community at this rate. We are not using technology the way we should; many hospitals are still using paper records, which contributes to the 24,000 people who die each year as the result of medical errors. Technology, properly used, takes pressure off workers. The technology is not going to save us any money, however it will mean better patient care.”

Andre Picard, noted health policy writer engages a guest at the Mayor's Inspire Series at the Burlington Performing Arts Centre.

Picard wanted to see the phrase “customer service” used in hospitals. “When” he asked, “was the last time you heard someone in a hospital ask: ‘Can I help you’ and when did you last see someone in a hospital look you in the eye”?

Picard told the 200 people in the room that the public/private health care debate is a phone debate. There are some health services that are best delivered by the private sector and paid for by the government. He explained that heath service is legislated in Canada and pointed to the Canada Health Act which sets out what the government will do and will not do, whereas in Europe the governments tend to regulate instead and their workforce is more efficient.

Our hospitals have in some cases become holding pens for elderly people, when they should be in their homes where they are more comfortable and can still get the care they need. Hospitals are the last resort and for the most part they are not safe places, Picard added.

The average age of Canadians in 1965 was 25 – now the average age is 47 and that number will climb for a few more years. In an earlier time hospitals provided acute care, patients when into a hospital to get treatment and were either healed or they died. With an aging population many need care for chronic conditions and that is not best delivered in hospitals. Many people have multiple disabilities in their declining years, but don’t need care in the kinds of hospitals we have today. The system we have is not built to deliver chronic care – community based service can deliver that kind of care.

There is no entry point into the medical system in this country according to Picard. If you have a problem far too many people head for emergency, because that is the only way they can get in. And once they get in – they end up staying in because there is no way out.

Picard believes that with a community based system there would be a team of people waiting to serve the needs of a patient and would handle everything from welfare through to home care for people that have those multiple chronic ailments. And most important to this team/community based approach would be a person known as the “navigator” who would ensure that patients got moved from level to level. If treatment in a hospital was necessary the ‘navigator’ would work with the team to ensure that happened. Better co-ordination is the future said Picard and more empowerment for staff, and equally important, accountability. “When they don’t do it well – remove them”, advised Picard. Picard made no mention of how removing staff would get done in the union environment we have.

The LINCs are, in Picard’s opinion, poor substitutes for the Regional approach that should be taken to providing medical care. The country, he said, needs a sound debate on what the public wants and what government can afford. “The goal of a healthy medical system” he said “is spending the money available wisely, delivering care so that we have a healthier population that can live a good life and have a good death”. It was clear from what Picard had to say that he doesn’t think we are there yet.

During the question and answer session Picard perhaps surprised many when he said he didn’t think Prime Minister Harper wants to have anything to do with health care and that Ottawa really isn’t that big a player in the game. They are responsible for aboriginal health care where everything – dental, optical – is included. The natives have the best health care in the country – why can`t the rest of us have that kind of care? Picard added that he personally didn’t think Harper wants to make his mark in health care..

A community health centre in Cornwall, Ontario got started this way: “It’s about taking care of our day-to-day health needs, as well as promoting a healthier, stronger and more sustainable community,” said Debbie St John-de Wit, the Centre’s Executive Director. It’s been almost a decade since the notion of a new community health centre for Cornwall was first conceptualized. Incorporated in February 2005, a dedicated and passionate community-governed, volunteer Board of Directors began evaluating the community’s health needs in order to develop a customized primary health care delivery model. The planning process involved several community engagement sessions and meetings. In 2007, the Board of Directors received approval from the Ministry of Health to proceed with the feasibility study, and in 2009 the Ministry approved for the construction of a new centre.

Picard closed his presentation saying that home care is safer, cheaper and people like it. The trick he seemed to say was the administration and delivery of health services into units that have populations of about a million people and allocate the funds to those groups and let them figure out what`s best for the community.

Picard made one very trenchant point, when he said the Canadian Medical Association speaks for the medical community. There are, said Picard “body part” interest groups. Every imaginable group is represented –heart, kidney, lungs, but have you noticed he asked “that the public isn’t represented”. There isn’t a Canadian Patient Association.

The medical business he said, needs some democratization – it isn’t a fair fight the way it`s set up now.

The reality he added is that there has to be some “private” in the health care field and Critical Illness Insurance was something that made sense. More than 22 million Canadians have some form of private medical care.

Our care patient service has to be delivered where the patients are – it could be delivered in a mall location if that worked.

Someone asked Picard what he would do if he were the Minister of Health and he responded instantly with – “well the first thing I would do is get rid of the Ministry and run the place with my cell phone from the car they would drive me around in”. “I would then transfer funds from the Ministry to the different regions that would be set up to deliver health services to communities across the country with no one grouping having much more than one million people within it”. One got the impression that Picard wouldn`t be building a lot of hospitals either.

As for Burlington and the Joseph Brant Memorial Hospital – Picard equivocated when asked if upgrading the hospital was the right thing to do. “More or less”, he said. For a guy who had very strong, direct statements to make on just about everything else he said – ‘more or less’ – was rather telling.

In bringing Andre Picard to Burlington to talk about the delivery of health care Mayor Goldring may have brought to the surface the need for all of us to take another really close look at how we make decisions. Is an upgrade to the JBMH the best thing for Burlington? Good on you Mayor Goldring for bringing Picard to Burlington – even if his comments will make your life a little bit more difficult – you did the right thing.